When I thought that The Outsider would be simply a very well-written character portrait – an unusual and unsettling pair of eyes through which to view the world – things become more complicated. She just wanted to know if I’d have accepted the same proposal if it had come from another woman, with whom I had a similar friendship. I said, “No.” She didn’t say anything for a moment and looked at me in silence.

She then remarked that marriage was a serious matter. Anyway, she was the one who was asking me and I was simply saying yes. I explained to her that it really didn’t matter and that if she wanted to, we could get married. I replied as I had done once already, that it didn’t mean anything but that I probably didn’t. I said I didn’t mind and we could do it if she wanted to. That evening, Marie came round for me and asked me if I wanted to marry her. He feels things to a moderate amount – the novel opens with his mother’s death, and the most he can muster up is that he would rather it hadn’t happened. He is not cruel or unkind, he is simply emotionless. Meursault sees the world through a haze of emotionless indifference. A lot of that style is due to the protagonist – Meursault – and the first-person presentation of his life. It was thus rather a delight to find The Outsider more in the mould of the detached, straightforward English novelists I love – Spark, Comyns – but perhaps most of all like my beloved Scandinavian writer Tove Jansson.

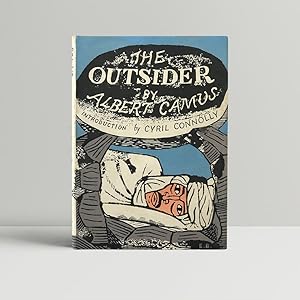

The title didn’t encourage me – I thought it might be very existentialist or, worse, in the whiney and disaffected Holden Caulfield school of writing. I have found some of it rather too philosophical for my liking, and there is always the spectre of ghastly French theorists I have tried, and failed, to understand. My experience with French literature – always in translation – has been mixed.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)